When actor and filmmaker Ben Steel came to Adelaide in November 2019 to present his documentary, The Show Must Go On, at the Mercury Cinema, he and I met before the screening to discuss his film. In the brightly lit cinema, we sat across from each other in comfortable red chairs, my voice recorder (and phone as a failsafe) perched on the chair between us as Ben spoke with empathy about what drove his exploration into the mental health and wellbeing challenges faced by those working in the entertainment industry.

It is certainly a topic that demands attention. For example, The Australian Actors’ Wellbeing Study in 2013 found elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in the over 700 surveyed respondents. Amongst the challenges reported by respondents were incredible financial instability and difficulty in getting regular work, travel and the associated time away from home and loved ones, the emotional and physical tolls of a role, problematic uses of alcohol to cope with stress and, indeed, the attitude reflected in the title of Ben’s film that the show must go on, even if one is experiencing physical or psychological difficulties. While many of these issues are not specific to entertainers, both the research and anecdotal evidence certainly points to them being certainly heighted hazards of working in the industry.

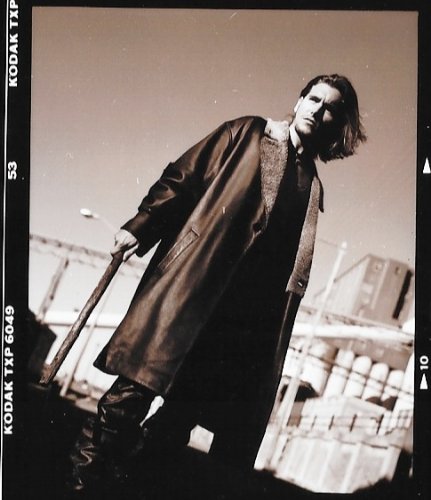

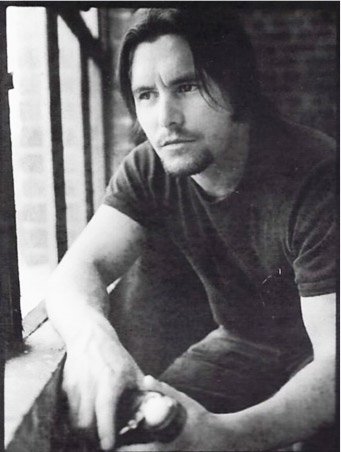

As writer-director of the film, Ben had initially set out to understand why so many creatives struggled with their wellbeing and to look at ways to prevent or tackle these issues. With camera in hand, he began by interviewing entertainment professionals from stage, screen, television, and music, both those who work in front of an audience and those behind the scenes. While Ben didn’t envision being in the film beyond some of the interviews, as the project took shape Ben and his team realised that it was his own story that could be a focal point of this exploration and a way to bring together the diverse thoughts of participants, including Sam Neil, Michala Banas, Jocelyn Moorhouse, Dean Ray, and Glenn Scott. And so, in the film, and in subsequent screenings as part of the Wellness Roadshow, where Ben travelled around the country to screen his film and lead discussions about mental health in the industry, Ben honestly shared his story.

Central to Ben’s experiences was how he navigated life post his star-marking turn as Jude Lawson on drama series Home and Away, for which he received a 2001 Logie nomination for Most Popular New Talent on Australian Television. When that role ended, he ventured overseas working as an actor, as well as behind the scenes. Returning to Australia, he found not only the work had dried up, but that he was struggling emotionally. In moments throughout the film, Ben lets us in to the depth of that struggle. At one low point during production, he tells us that he felt his work on the film was “a mission to help other people”, but then asks, “But how can I help other people if I can’t even help myself?”. With therapy and support, Ben worked through it, learning much about himself and what keeps him well. Through his own struggles and understanding of the world he investigated, he provides a space for his interviewees to be honest and forthcoming with their own stories. In the process, he has also given us a beautiful film.

It has taken me significant time to publish this interview. If asked why, perhaps I can use the standard reply of 2020-2021, “Because COVID”. As work responsibilities intensified, our chat on my to-do list and my anxiety would rise as I remembered how much I wanted to get this out there.

If anything, however, the delay may be strangely perfect. As Ben and his team adapted to COVID-19, with webinars and online screenings during 2020 and 2021, the core issues of the film have become focused. Paradoxically we have realised the necessity of the arts in our lives as we bunker down at home in front of our TVs and devices, but the creatives themselves have had limited support from government in Australia and overseas as the industry has shut down or been severely affected. If anything, watching the film made me, and I hope you, want to support the arts more when we reflect on how much joy we get from live music, live comedy, art, theatre, TV, film…and the list goes on. Yet, most creatives are living a very hand-to-mouth existence, with the Wellness Study revealing that around 40% of respondents were earning less than $10,000 a year and around 20% can be considered below the poverty line. What comes across in Ben’s films is not only the love creatives have for their craft, but the necessity for society to have a vibrant arts culture. As actress Wendy Strehlow told me in a previous interview, “I am passionate about the vital role the arts play in society. “Holding the mirror up to nature”, so to speak. Without a healthy and thriving arts culture we are spiritually bereft”.

Why I think Ben’s film is relatable and audiences will find commonality between the film and their own experiences, even for those not in creative industries, is that it shines a light on a lot of the risks for mental unwellness for all of us. Regardless of career, upbringing, and experiences, we are often not taught about psychological care or wellbeing as we navigate our worlds and pursuits. It was Ben’s hope that the film could start a conversation about such matters, and I hope that you enjoy ours.

Adam: Tell me about the Wellness Roadshow. How long has it been going and where have you been so far?

Ben: We launched it on my birthday, on the 9th of October, straight after the ABC premiere. We’ve had screenings in Melbourne and Sydney and Newcastle, and now we are in Adelaide. Next year we’ll be heading to the other states, going to Perth and Hobart and the Gold Coast.

Adam: And you’re doing this over the next 12 months or thereabouts?

Ben: Pretty much. It’s just that rolling thing. We’re doing the capitals first and we’ve just started to get little pockets of funding that can take us to some regional centres as well. We’ll just keep rolling it out as much as we can, spreading the word and getting people talking.

Adam: The film screened on ABC back in October and you’ve been traveling around since then. What’s been the reaction to the film so far?

Ben: It’s been amazing. I always hoped that it would connect with people and that people would respond. I guess it was kind of a no brainer that creative people or people within the entertainment industry would probably connect to it. But I was always hopeful that it would reach outside of that, which it kind of has – which is amazing. Collectively, as a team, we’ve probably received now over 100 emails, texts, or whatever, from people saying it’s actually saved their lives and they’re getting help.

Adam: That’s fantastic. Were you expecting that?

Ben: I was hopeful it was going to make a difference, but to actually hear it and feel it, makes me really happy. It’s quite overwhelming that what we’ve been able to make has had that impact. There’s been hundreds and hundreds “thank you for doing it” kind of emails, but the ones that really bowl me over are the ones where people say “I’m actually going to get help now” or “It’s saved my life”. Literally those words. And you go, “Thank God, that means we’re really helping people”.

Adam: It’s the kind of film that makes sense that people would contact you. But often you put something out there and you wonder, Is anyone listening? Is anyone watching?

Ben: Yeah, definitely. I guess because it’s such a personal film and all the cast that were involved, who beautifully and generously gave their time and they were so candid, they were just so open – that’s what people are really responding to.

Adam: Disclosing depression or anxiety or any mental unwellness is difficult. Was it difficult for you starting the film – although you weren’t initially going to have such a big role compared to what it ended up being – knowing that you would have to disclose something about your own story or ‘come out’, so to speak, about it?

Ben: I guess initially I didn’t think I would be [Laughs].

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: Probably the first part of that is, at the beginning, I just didn’t have the awareness. I hadn’t started my recovery. I hadn’t received help. My awareness level of how bad I actually was, or how much I was struggling, I just didn’t have the awareness level. So, to have that – I wouldn’t have even thought.

Adam: That far ahead.

Ben: Yeah. It was probably – I mean we had a big team meeting probably about eight months in when it became apparent that my story was central to this film. Up until that point, it was me interviewing people and talking and I was going to construct something together based on all these opinions and solutions. I wasn’t in it. There were shots where I was on camera, but it wasn’t my story. So, we had a team meeting when it became apparent that “You’re the through line here, Ben. That’s what people are going to connect to, your story, and then all these other things feed into it”. Probably at that point, it was a little bit, Am I ok with that? I think since I was asking other people to put themselves out there, I’ve got to be able to do that myself. I guess being an actor and being on screen, I didn’t have that barrier to overcome in the sense that I’m fine to see myself on camera, or hear my voice, which some people behind the scenes.

Adam: Are a bit reluctant to do.

Ben: Yeah. I didn’t have any of those issues. And then it was only probably two weeks after we finished making the film – editing was done, it had been approved by ABC, and the post-production people were doing all their magic deliverables and making DCPs and all that. I was away on holiday and I kind of went, “Oh shit, my story is going to be out there in like two weeks”. And I was like “Ooh, ooh”.

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: And it just gave me a little bit of a butterfly of nerves. I mean, I was fine. Everything in it is me and it’s what happened. It felt like I need to tell people that story.

Adam: I think you’re right that the focus is really you because you’re holding all those stories together. I could appreciate if you had reluctance because, as we said, it’s hard enough to disclose regardless, but you’ve been in the network machine of publicity and there’s a very structured way of having publicity. I think it’s great you could do it.

Ben: Thank you. I guess that was so far away from my current reality anyway.

Adam: Of course.

Ben: To be honest, I didn’t really think of the career consequences, if any. At a certain point – I mean, in the beginning, I was being driven by there being some people really struggling and I want to know what’s going on. Then it reverted to “I’m actually struggling, I need to find these answers for myself”. And that trumps any kind of I wonder what people are going to think about me [Laughs].

Adam: [Laughs]. That’s great. That leads in quite well to what I wanted to ask. When you started filming, you knew you weren’t good, but you weren’t aware of where you were. Was it in your mind to try to unravel what was going on for you?

Ben: Not in the beginning. It was only after I started becoming aware. In the beginning, so I left Home and Away – got dumped [laughs].

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: Then went overseas doing the UK thing like so many ex-Home and Away and Neighbours people do. So, I was kind of milking that and working that for all I could, riding that particular wave, and just kind of pushing and pushing and pushing. Then at a certain point – I think it was about nine years I was away – I came back to Australia. I wasn’t expecting there to be a welcome home party or anything, but I did achieve some things overseas. I made some shows and was in some films and all that kind of stuff. And I guess I was expecting the transition back into the industry to be a little bit easier than what it was.

So, I was aware of that struggle that I felt like I was outside the circle. And at the point I put it down to, Well I’ve just been away too long, people have forgotten about me. I hadn’t maintained all those relationships and friendships and networking that you need to do. Maybe part of it was that, but I think more of it was because I just had this huge identity crisis about to blow up and happen and I was so caught up in my identity as an actor and pursuing that, that I wasn’t actually being a real person. So, I think that was probably getting in the way of my career more than anything.

Adam: Sam Neill talks in the film about this idea that it is perhaps healthier to have an approach to acting, or any performing, as, “That’s what I do, that’s not what I am”. He describes it as separating yourself from your profession. So, as opposed to saying, “I’m an actor”, to say instead, “I’m Ben and I act”. Did you find in talking to people that this is often a pitfall for actors? Because there’s such a drive to get there, you really have to work at it consistently and it’s probably impossible for it not to become pretty much your identity

Ben: I think there’s two parts to that. I think, one, is that through the training we get, whether it’s behind the scenes or in front of the camera, you’re made abundantly aware how slim the chances are you’re going to succeed. So, you have to really just put everything, your focus, on it. When you’re doing that and you’re not having a social life, and you’re missing weddings and funerals and real-life things, or you don’t have hobbies because you don’t have time, how could it not become your identity?

I think the other factor to it is because there is so much rejection, and there’s oversupply and under demand as far as work, how do you deal with that rejection? You deal with that rejection by creating this wall, or thick skin around you, and really just saying, “Well, this is who I am”. You’re kind of building these walls that “I’m an actor and this is all I am. I’m just going to keep doing this”, or whatever your job is. I think for those two reasons that’s why it’s a no-brainer that a lot people in entertainment have identity issues. But I think it’s also across the board. I think a lot of people out in the wider community also do. A perfect example is when you’re raising kids and you become a parent and that’s all you are for a substantial chunk of your time.

Adam: It’s not a role, it’s an identity.

Ben: “I’m a parent, I’m a parent, I’m a parent”. And then the kids leave home. And then you suddenly have an identity crisis.

Adam: “What the hell do I do now?”

Ben: Yeah. Or you’re a corporate CEO and you’re working towards this and you’re building a company, you’re building a company, and suddenly it goes bankrupt and nobody returns your calls and nobody cares about you anymore, and you can’t fund anything, so who are you anymore? You’ve lost your identity.

Adam: That’s perhaps why the film is reaching all sorts of people. There are some unique issues with actors and the entertainment industry that you cover, but there’s also a lot not specific to actors – the idea of identity and overinvesting in your job. When I was watching it, what came up for me is this idea of perfectionism.

Ben: Yeah.

Adam: I would imagine actors are often quite perfectionist and whether that’s a personality trait they bring to it or whether it’s something the industry breeds because you have that slim margin, you’ve really got to be on, you’ve got to be ready. But then what some of your interviewees found – and what I find with my perfectionism, which leads to nothing but anxiety most of the time [Laughs] – is I get to wherever I imagine I’m going to go. And, first, it’s “Fuck, I’m exhausted” because I’ve near killed myself doing it. And then after that it’s like, “I’m not going to be able to maintain this”.

Ben: Mmm.

Adam: “How do I keep myself on top here?” I think that came through with some of the people you speak to. Even when they had this success, it’s like, “Is it going to be taking away from me?” Or, “How do I maintain this?”. Or “I’m an imposter, they’re going to find out sooner or later”.

Ben: Definitely. And again, I think that’s quite common across the board. Maybe it’s part of us breaking down mini steps along the way to success, and certainly within the entertainment industry there’s no one clear path to anywhere. But maybe a quite common belief is “I just need to get this one big break. And then once I get there, everything is going to be fine. I’m going to have all the money I need. I’m going to be as happy as Larry. The next opportunity is going to come easier”. And da da dah-dah. And, as you allude to [Laughs

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: and what’s in the film, when you get there, there’s a whole other slew of things you’ve got to deal with, or other fears or concerns that, “Now I’ve got it, what happens if it gets taken away from me?” Or there’s just so much pressure at that point.

Adam: Yeah

Ben: But it kind of again makes sense that we probably, as humans, put things into little boxes. We just focus on that first bit and then I get to that bit, and then “What’s next?” And I think it’s also society kind of pushes us and feeds us that way, like “More, more, more, more”.

Adam: Absolutely.

Ben: And you hear it all the time – enjoy the journey. It’s all about the journey, not the destination. But it’s hard to live by that principle.

Adam: It is, isn’t it? You’re not taught to look at what are your values compared to what are your goals. Your goals are something you achieve, like you can get on to Home and Away, great. But what are your values about creativity or contribution or whatever else? I kind of wonder – I’ve spoken to a few actors about this, and I think a lot of jobs are like this, but particularly with creative people – when I write, often it’s an extension of me, it’s very tied into identity. So, when you get rejected, it feels like a very personal rejection. I’ve spoken to actors who tell me that it feels like a rejection of them, rather than “Hey, there were 10 actors, and it just turns out that you’re not the one that’s right in the director’s mind. It doesn’t mean you’re not good”. It feels very personal.

Ben: Yeah, definitely. I think you’ve hit it on the head there, what we do. Unlike other industries, we are bringing so much of us into it, there’s a big amount of emotional vulnerability, like Glenn Scott says in the film, there’s so much emotional vulnerability. So, if you are rejected, it is you they are rejecting, it’s your creative pursuit – like, if you’re a technician, it’s the work you have done, or not done, that they are not happy with. Because you are putting your heart and soul into it, and you so closely link what you’re doing to you, that they’re not just rejecting what you’ve done, they are rejecting you. Most other jobs, most other careers, I think there’s more separation between that. Not all the time, but I think most of the time.

Adam: Yeah.

Ben: And I think performers again take that step just even further, and potentially probably comedians have it the most in the sense because they have created the story as well as performing it. And if you’re not funny, if they are not laughing at it, it’s a real failure.

Adam: Yeah, watching Andy Saunders, who is a comedian, in the documentary. That’s interesting you say that. When you were talking to Sarah Walker, who wrote for Home and Away, it’s your character, but it’s also her character. With comedians, it’s them out front, it’s often their stories.

Ben: Mmm.

Adam: I was speaking to my friend Gavin Harrison, who was in Home and Away probably ten years before you, he played Revhead.

Ben: Yeah, yeah.

Adam: And this picks up from what we were talking about before. Among the reasons he transitioned out of acting was that, he said, “I wasn’t really comfortable not having control of where I was going in my life”. He’d gone to America and ended up in a whole lot of TV shows and films there and he was so busy auditioning – it was actually Gavin who said, “That’s the part of acting where you can have 10 good actors, but only the person who is completely right in the director’s mind is going to get booked”. He told me that Jane Nagel, who did publicity for Home and Away, gave him some useful advice that, “there’s the person, the professional, and the product, and that these three aspects of my life should be viewed as such when I was doing certain things”. That helped him, although I’m sure he would admit how hard it can be. When you spoke with Dean Ray in the documentary, for example, when people say something like, “Hey, you got fat”, it’s pretty hard not to take that personally, no matter how much you realise you’re a public person or personality.

Ben: One bit that didn’t make it in the doco – my dear friend and Home and Away actor, Ada Nicodemou, said, which is similar down that path, “It’s not about me, it’s about the character that I play and the show that I’m in. They’re famous, I’m not famous. That’s what people want, that’s what people need”. The show is so much bigger than us.

Adam: Yeah.

Ben: I think that’s quite a healthy way to look at it. Regardless of whatever art it is, ultimately “the song” is the star [Laughs],

Adam: Yeah [Laughs].

Ben: the album is the star; the front person is not. The end result of many people’s work is the star, it’s where the fame is attached. Having that healthy separation from, you know, doing this interview with you, or doing Sunrise, or whatever, it’s actually not about me at all [Laughs]. It’s really helpful to go in with that mind. And that’s what we want, that’s what we love, that’s what we’re selling, that’s what we’re pushing, that’s what we’re all working towards, that’s what all these thousands of creative people are coming together to work on – the thing that is the star, it’s the product, it’s the show.

Adam: What do you think are some unique challenges for performers’ mental health?

Ben: If we are to compare entertainment to wider society, the biggest thing is – like what we’ve spoken about already – just the emotional vulnerability that we have to go to for our work. The sensitivity that’s actually involved in doing what we’re doing. Even if you are a technical person on the crew and you’re looking at lighting or something like that, it’s such a beautiful, delicate – you’re putting your heart and soul into it. It can be quite a technical thing, but there’s imagination and creativity and you kind of then are invested in the thing that you’re doing or building.

Adam: And you’ve worked in lighting as well.

Ben: Yeah, I did lighting.

Adam: The film was beautifully done.

Ben: Oh, thank you! Or you’re constructing a set, like you’re the chippy, you’re the carpenter on the set, you could make far more money out building houses or buildings, rather than working in our industry. They’re drawn to it because there’s something else, something magical, they’re expressing their creativity in a different way, or they are getting to work on different things

Adam: Yes.

Ben: Everybody in the industry has that – that emotional vulnerability and sensitivity and connection to what we’re doing. I think that’s a big one. The other big one that I found is that a lot of the pressures that we face – there are some little weird, little quirky ones that no other industry has, like talking in public, although some other industries have that – there’s quirky things like auditioning, auditioning, auditioning. Other industries, you could be getting job interview after job interview. A lot of what we go through can apply to other industries, but a big thing is the accumulation of many pressures happening at the one time. I think that is quite unique to our industry. Not only are you putting your heart on the line, you might be working at night, and you’re working interstate,

Adam: Away.

Ben: Away, and you’re not getting paid that well. So, you’ve got multiple pressures that most people, if they had one pressure, they’d freak out. But our industry, we’re facing multiple pressures all at the same time. I think that is unique to our industry and that’s why our stats are larger than the general population.

Adam: An example of what we’re talking about is when Jocelyn Moorhouse discusses in the documentary the pressures of her film not getting made, but then two of her children are diagnosed with autism. It’s on top of, on top of, and on top.

Ben: Yep. Ultimately, at the end of the day, all of this, all of what we’re talking about, mental health and wellbeing, mental ill health, it’s a human issue. We, in the industry, are human [Laughs]. There’s just some stressors or pressures that may be a little bit more weird or different or hard for the rest of society to understand.

Adam: And there does seem to be that gap a little bit

Ben: Yep.

Adam: Some people have this idea that actors are sitting in the mansion. For the vast majority of actors, that’s not the case. For the vast majority, it’s a job, and there is instability and all those sorts of things. I love when some American actors post their residual checks on Facebook and they are getting a cent.

Ben: [Laughs].

Adam: A cent residual for a movie. Perhaps there is a little bit of a gap and maybe the film can help people to understand a little bit better that perspective.

Ben: Yeah, and I think that was part of the reason as well – and that’s why having my parents in there is such a good thing because I think many people outside the industry could maybe think down the lines of my parents. Or they are parents themselves to creative kids. So that’s why having them in there was so important to me, to give a bit of a voice and a personality to those opinions against some of the creative things. But then also some of the things they’re bringing up like, “Get a different job, just leave, do something else”. It’s hard to do. And funny enough so many people who have tried counselling or therapy and hadn’t found the right one – and I’d suggest people keep trying until they find the right one because they will be there –

Adam: For sure.

Ben: I had to go through several to find the right one. The counsellors don’t know how to – they seem the problem being the industry, so just get out the industry [Laughs],

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: which is kind of short-sighted because if everybody just got out of the industry there would be no entertainment, so you know.

Adam: And that doesn’t take into consideration the things that the person does get from the industry, in terms of their values and what they want to achieve. But also, perhaps, practically – and again speaking to actors and performers I’ve spoken with before – you’re so driven, even though you’re expected to work multiple jobs while you’re acting, you’re so driven or you really have to focus, that it’s not that easy – for many people, they might think, I haven’t necessarily built some other things to be able to do, so even if I wanted to exit, how can I exit? This is all I’ve ever done.

Ben: I interviewed Susan Eldridge who’s an amazing woman at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music. She didn’t make it into the film, but we’ll be releasing some additional content with her, as we will with some other people that aren’t in the film because there were so many amazing people, I just couldn’t fit everything in. She’s devised a couple of – well, she’s devised an amazing program out there – but among some key things that I learnt from her was focus on living a creative life, rather than having a creative career. That doesn’t mean that we can’t make this our profession, or we can’t make money from it. But when we’re valuing it like other industries and other professions, we’re kind of setting ourselves up to fail. Because there’s only a very small amount of people who can sustain a career out of this, so therefore when we aren’t sustaining a career, where does all the negative energy go? It goes to us because we feel that like we’ve failed, or we’re not good enough, or we’ve missed the boat, or we’re getting too old now, we can’t do this anymore, or whatever. But what we can actually do is live a creative life every day. So, focus on living a creative life rather than ‘pursing a creative career’ is one thing that she taught me. The other thing is rather than having a day job or a Plan B or a backup plan, or any of that kind of stuff, she says, “Have two Plan A’s”.

Adam: That’s great.

Ben: Focus on your creative life, and then focus on something that can bring you a certain amount of stability – and it can actually be another creative job, it can actually be creative industries – and that allows you to be able to pay your bills and do everything else or achieve your other goals, whilst you are still pursuing living a creative life.

Adam: Absolutely.

Ben: One thing about performers, I think most of us have multiple jobs. We’re not just pursing one thing. So, I write, I direct, I produce, I shoot, I make stuff across the whole spectrum of entertainment, not just in one little niche. I coach actors, I work with actors, I shoot their self-tapes, I do many different jobs within the industry. And all that cobbled together in the gig economy is enough to support me to keep pursing a creative career, whether I’m auditioning or whether I’m writing something or whether I’m making a documentary. I’m not saying I’m the success story, but I’m using that as an example.

Adam: Yes.

Ben: Because again, at the beginning, I didn’t have that awareness that I actually was going OK. Once I had that awareness and gratitude – Oh fuck, I’m actually going OK. Look at all this awesome stuff around me – I started to feel better.

Adam: I was going to ask you about that because you’ve done a whole range of other things when you were overseas and even before that. Even before you started on Home and Away.

Ben: Yeah.

Adam: Was that something that kind of just happened or was that sort of a guided move?

Ben: Funnily enough, I wanted to leave school after year 10 because I was already acting when I was a kid at school. I was already working; I was already in the industry. I already knew more than my media teachers at school because I was doing it – arrogant little fucker [Laughs].

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: My parents said, “No, stick at it”. They were the kind of ones that planted the seed of having other stuff that I was interested in. They weren’t in the industry, they didn’t know anything about the industry, so it was really a fortunate bit of advice. So, I started getting interested in behind the scenes and shooting stuff, and bought a camera and started making little films, started doing subjects at school that were that way. And then all my work experience and everything like that was about that. So, when I left school, that’s what I did. I just started working in the industry in other areas. That was cool and exciting, and I was learning stuff.

That was my path. There’s no right or one way to do it. But I think – so, with the multiple things I was doing when I was at my darkest, I just didn’t have the appreciation because again my identify was so linked with – my definition of success and identity were linked into I have to be an actor in a studio film or a network show. If I’m not in that, then I’m a failure. The fact that I was working with actors, Nup, well that’s not good enough. Why am I not being able to do that? I was so negative about the amazing thing that I was maintaining and being able to live a creative life. So that’s a big thing, I think, is kind of getting your expectations in check and actually redefining your definition of success. Because if you can support yourself, you can still keep doing the thing you love every day and be plugging away. That’s a success. Winning an Oscar, winning a Tony, winning an Emmy, winning Logie, that’s not success. Being able to still do what you love and find a way to support yourself and have a whole full life, that’s success.

Adam: I write but I’m not in that industry. But what my therapist, for example, said to me was that you can’t expect to get all your creativity or all the want to contribute something out of one thing.

Ben: Mmm.

Adam: And maybe the whole difficulty I was having in a former job was that I expected to get all that from one thing. A: Who does? And B: Is that going to be healthy or sustainable?

Ben: Definitely. The other thing I want to say about the Plan A-Plan A, your other Plan A can actually be out of the industry because some of the skills that we have as creative people, other industries want. So, what is wrong with having a job in another industry using aspects of your creativity? Again, it’s about thee awareness. The fact that we can think outside the box.

Adam: Yeah.

Ben: Many people in brainstorming kind of situations want that skill in their team. Obviously, performers can be very confident, they can work with scrips and do telemarketing and do things like this. Again, if we’re looking at that rather than “Ugh, I’m just a telemarketer; I’m not being an actor today”. Well, you are using some of those skills that you need and you’re honing those skills. We’re so good at focusing at minute little details, but also looking at the big picture as creative people. That’s part of our process. We’re doing that all the time. Again, it’s another skill that other industries would die to have in their workforce. We can actually make good money on the side in other industries. The other great thing is because most of us are freelancers, and what’s happening out there in the big wide world? It’s becoming a gig economy. The world is turning in a gig economy. We’re already 10 steps ahead [Laughs].

Adam: What you might have seen as a deficit, is not a deficit at all.

Ben: Yeah, this constant chasing work and being on the go. As exhausting as that is, we’re – like, that’s part of our DNA now. So, as we’re transitioning into a gig economy as a society, we’re kind of a step ahead as creative people. Looking at the positive and really kind of being grateful for that opportunity, rather than going “Ugh, what am I doing next and dah, dah, dah. Thinking, Actually, I’m ahead of a lot of the population.

Adam: We see that with a whole lot of creative people. I mean, you even seen some creative people become counsellors or therapists.

Ben: I think it’s about that awareness. For me, a lot of I think my struggles were just based on beliefs that weren’t the whole truth or weren’t any truth at all. I just held on to them for whatever reason. It’s quite a hopeful thing now that you can actually – once you kind of have a look at the real issue and what’s going on for you and what’s underneath that and what’s underpinning these beliefs, you kind of unpack that and go, Actually, that’s not true – this is more the truth. So, getting that awareness. And if I can do it, anyone can with help.

Adam: I think the film and a lot of what you’re talking about is really speaking to what so many people experience, regardless of whether someone is in the entertainment industry or not. You’ve spoken just now about the idea of really understanding your thinking, and that’s something we don’t teach people. We teach physical health, but we don’t teach people to go, “I’ve got a million thoughts in my head. Perhaps I don’t need to buy into every one of them”.

Ben: Yes.

Adam: “Which one’s are useful? Which ones are not useful?”. All that kind of stuff. From what you’ve learnt for yourself, and from what you’ve learnt with talking with people – bearing in mind everyone’s journey is different, what do you think we’re missing out in terms of what we’re teaching people?

Ben: I think for creatives or just for the wider community at large, it’s kind of putting your personal emotional development at the forefront of your learning and your education from, you know, your parents. So, parents getting better skilled at this kind of language and how to do that because then their children will be a little bit more prepared.

Adam: Yeah, they’re providing that framework.

Ben: Yep. The communities that we’re then involved in and the wider support networks around that child. Then they go into the education system. Again, the teachers and the school and the infrastructure around that child as it grows and develops Then the tertiary institutions or the workplaces. So, the more and more emotion and emotional intelligence and psychology.

Adam: Self-reflection.

Ben: Yeah. When that is more in the forefront and valued as a big part of who we are.

Adam: As important as all sorts of other things.

Ben: Right. Because if you kind of separate – what is it when it’s separate? It’s that your body and your physical health is more important. Ah, no [Laughs]. Or that finances and accumulating more wealth is the most important, which is how capitalist society works, right? But no, you can have all the money in the world but you’re eddying of cancer and you’ve got a psychological problem.

Adam: And nothing’s ever good enough and we keep on the treadmill.

Ben: And I’m not saying the emotional and psychological health should be superior to the physical or to other exterior forces, but at the moment it’s barely a blip on the radar. So, I think more people talking about that and actually going, no, self-development and looking after yourself and checking in with yourself and your psychology and getting to know yourself and getting to know other people and all that – that’s a really big thing.

People on their deathbed aren’t kind of worried about how much money they’ve got in the bank that they can’t spend anymore. They’re worried about the relationships they’ve created and the impact they had in the world, and the friendships and the love and the stories that they’ve shared. And that’s all human emotional and psychological, right?

Adam: Yeah. I think that the absolute core of what you’re saying, you know this whole idea of self-reflection, in the service of knowing you are, not only makes you – a more rounded person, a happier person, whatever you want to call it, better relationships, whatever. I guess it does also feed into those relationships because the more you understand yourself, the more you are going to understand other people.

Ben: To have compassion for other people.

Adam: Yeah, compassion for someone else’s plight. Actors use that every day – they use compassion, they use empathy to get themselves into someone else’s head. Perhaps sometimes what the problem could be is that you’re being asked to tap into a whole range of emotions and life experiences that you may have not processed yourself and then all of a sudden you have to use this and put this out every day. I think unless perhaps there’s been that understanding or development of some sort of insight or where this fits into my bigger story, it may do a little bit of harm.

Ben: Yeah, definitely, I think that’s another big issue for actors and maybe other performers. There’s a lot of training and attention given to getting into character in whichever technique you believe the best for you to get into character, but nobody teaches you how to do get out of character or to de-role or to debrief or kind of leave that behind. If you are dealing with pretty intense, vulnerable, psychologically challenging worlds and material and situations and emotions that you have to put yourself into, it kind of makes sense that you have to be a pretty strong person at the beginning to kind of cope with that. And even still, you still might have challenges.

Adam: Yeah.

Ben: But if you are going through something at that point and you’re thrust into an environment like that where that’s your job, that’s what you have to do, chances are you might not come out the other end so healthy.

Adam: I speak to people outside of this industry, nurses, for example, and they talk about the idea that they’re constantly with other people’s emotions. They talk to me about how when you get yourself into the other person’s head, it’s absolutely fine to feel something for someone – so you feel scared for someone, frustrated for someone, or concerned for someone. But when that kind of self-other separation breaks down and they become personally distressed, they know they’re not going to be able to do their job so well. Also, there is that sort of hangover – they can’t just go home and say, “OK, that’s it now”.

Ben: Mmm.

Adam: And I imagine that might be similar for actors. How do I debrief out of that? Whether it’s talking to other people, or whatever. How do you deal with that real intense emotion and getting into someone else’s head?

Ben: Yeah, definitely. It translates to a real psychological thing, which is called vicarious trauma. So, you’re vicariously being traumatised. It’s not your trauma, but it’s some other trauma. Journalists in war zones go through this, so they’re standing back but they’re watching some horrific shit happen in front of them, and they have to report on that. Or, in my case, it could be argued that in making this documentary, I was getting traumatised vicariously. Because I was hearing people’s stories over and over again and I was watching stuff.

Adam: How did you deal with that?

Ben: Yeah, it was difficult. Um, I think fortunately for me, as I kept going further and further along through the filmmaking process, I was getting more and more support, and whilst there were times that I was really bad and really dark, I was starting to develop the skills that I needed to kind of help me get through that and knew the support was around me.

Adam: And were you going through counselling or therapy at the time?

Ben: Yeah, Yeah.

Adam: And we see some of that through the film.

Ben: Exactly. I dealt with it the best way that I could. But it can’t be underestimated, vicarious trauma.

Adam: When you speak in the film to Home and Away writer Sarah Walker, you bring up this idea that in a way you hadn’t let go of your character Jude. I’ve asked other actors this – is he an easy character to live with and do you think you have?

Ben: I think with Jude and the thing that – I mean, maybe it was quite close to me. He was really caring and really sensitive. He was looking after his little brother – different to me, but he had family issues, so he really kind of had to grow up pretty quickly and then he took in a foster kid, as well. So, he was really kind of caring and nurturing. And I guess that’s part of me and my personality as well.

Adam: Yeah, I can tell by the way.

Ben: [Laughs]. Thank you. I think it was hard to let go for me because my identity was so closely linked to what I was doing and suddenly I’m not doing that anymore. I think it was hard to let go of Jude because I hadn’t had conversations with other actors about letting go of characters before. I hadn’t thought about the bigger kind of things that you go through when you go through such an amazing experience like Home and Away. When it comes to an end, it’s quite common for whatever role you are in in the industry that when the show comes to an end, there’s a thing called post-show blues. You get a little bit sad and flat.

Adam: Even a grief some actors talk to me about.

Ben: Yeah, a grief, yeah, exactly. And those kind of things people don’t really talk about. We don’t really talk about that stuff. I certainly hadn’t had conversations. I think they were the main reasons why it was hard for me to let go of Jude, until ultimately going on this journey making the film and kind of unpacking the bigger and wider issues of the industry. But then, more intimately, unpacking my own issues and resolving that, so I could finally let go of that now and look back with fond memories of that whole time in my life

Adam: And being proud of it as well.

Ben: Yeah, being proud of it and, yeah – and I think, like I said in the film, if I didn’t have the Home and Away experience, if I didn’t have the getting dropped from the show and the subsequent battles and struggles that came from that, and my identity, and my struggles with all that, I wouldn’t have been at that precipice of struggling so much that drove me to make this film. I wouldn’t be there.

Adam: And not that we wish, you never want to wish these things happening to you.

Ben: [Laughs] No but, it’s, yeah.

Adam: But it’s which way you’ve taken it as well. Do you learn something from it? That’s very flippant to say it that way, but it’s really true. It’s what do you do with this?

Ben: Yeah, definitely, and I think I’m just fortunate through the people I have around me and the situation that I was in, everything kind of lined up and the skills that I guess developed behind the scenes that I could actually go off and make this film. It was the perfect outlet for me to do that because that’s what I do. I make stuff, you know, I do things. So, I just started doing it. I didn’t think about making a doco, I just started doing it. I thought, Oh yeah, I think I need to speak to people and I’m going to start filming it. And it just started to grow. It’s part of me and part of my process. Other people aren’t that way, and their journey is different.

Adam: That leads into my last couple of questions. Where do you see your identity today?

Ben: Mmm.

Adam: That sounded so Barbara Walters!

Ben: [Laughs]. No! Yeah, I mean – I’m so many more things than just an actor is, I guess, the core revelation.

Adam: Mmm.

Ben: And I’m just more appreciative and grateful for everything that I have and am.

Adam: Yeah.

Ben: So, I’m a pretty shit surfer, but I love it [Laughs].

Adam: [Laughs].

Ben: I’m a brother, I’m an uncle, I’m a son. I’m so many different roles, you know. I’m a friend. So I think it’s because when your identity is so closely linked into the thing that you do, the availability and just the emotional vulnerability that you have for all the other things on the outside, like friends, family, activities, hobbies, experiences, life, joy, parties – like everything is just so limited because you’re focused on that. I’m just experiencing life much more, so much more. I guess my identity is much more whole or much more full now than what it was. It was very shallow and narrow before.

Adam: That’s fantastic. I guess the final thing is what’s next?

Ben: [Laughs]. So, yeah, just continuing on with the beautiful roadshow and getting out and just trying to have as many conversations as we can about this. At the same time, surfing as much as I can because it just brings me so much happiness and joy and I love it! And I’ve started developing the next doco.

Adam: Awesome. That’s fantastic.

Ben: Awesome, brother – thank you.

The Wellness Roadshow continues through 2021. Full details are available at The Show Must Go On website. Please also visit the documentary’s Facebook and Instagram pages, and stop by Ben’s Instagram page for pictures of Ben, his dog, and beaches.

Images used in article courtesy of Ben Steel.

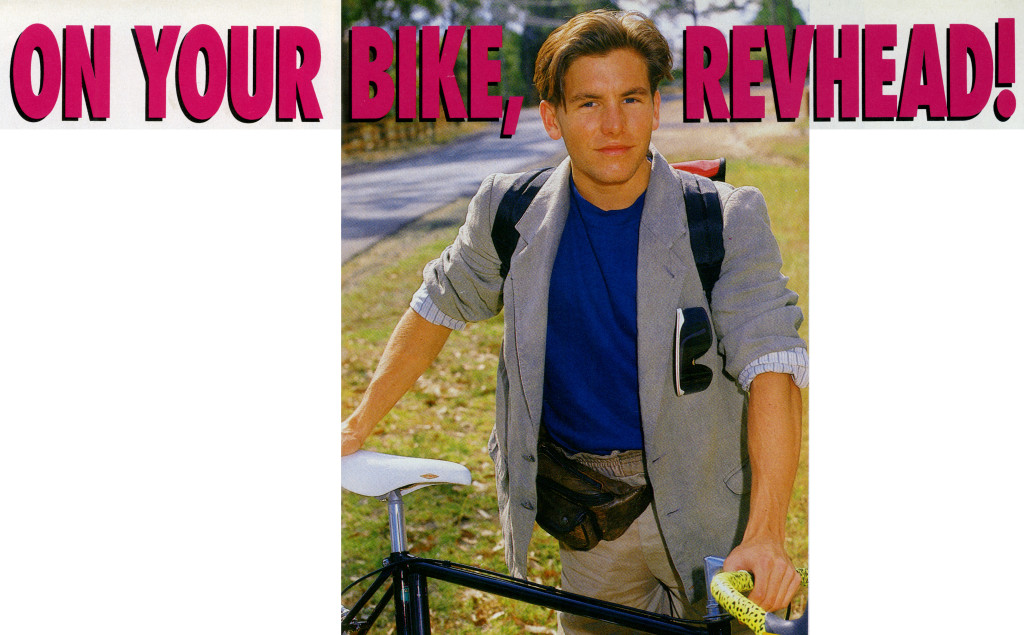

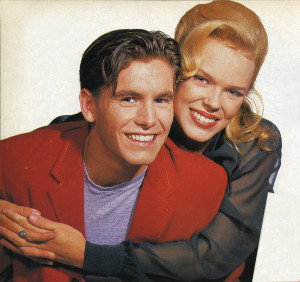

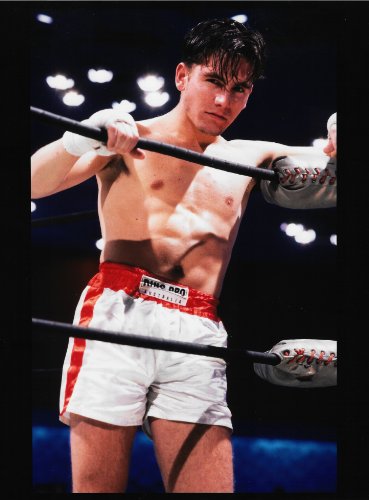

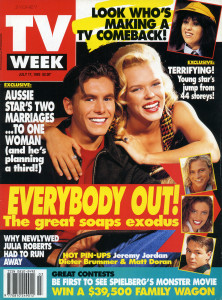

Gavin Harrison has always worn many hats. Of course, one of them was acting. On Australian television he played cyclist Hugo Strzelecki on the Seven Network’s revered drama series A Country Practice. Before that, he had several stints on Home and Away as Morris “Revhead” Gibson, one of the soap’s first bad boys. At the moment, Gavin’s main role is as a producer with his own advertising production company, Section9 Productions. The Los Angeles-based company engages in global print campaigns for everything from Kia to BMW to Tesla in the automotive industry, to Absolut Vodka, American Airlines, and Philips. It’s no surprise to find that it is a “full-service” company, meaning Gavin and his crew are involved right from pre-production, to shooting, and then to post-production. That includes scouting locations, casting, co-ordinating production, lighting, and working alongside photographers. After all, Gavin has worked in all these areas at one time or another, and has done so since he was 15. He’s clearly happiest when he is doing multiple things.

Gavin Harrison has always worn many hats. Of course, one of them was acting. On Australian television he played cyclist Hugo Strzelecki on the Seven Network’s revered drama series A Country Practice. Before that, he had several stints on Home and Away as Morris “Revhead” Gibson, one of the soap’s first bad boys. At the moment, Gavin’s main role is as a producer with his own advertising production company, Section9 Productions. The Los Angeles-based company engages in global print campaigns for everything from Kia to BMW to Tesla in the automotive industry, to Absolut Vodka, American Airlines, and Philips. It’s no surprise to find that it is a “full-service” company, meaning Gavin and his crew are involved right from pre-production, to shooting, and then to post-production. That includes scouting locations, casting, co-ordinating production, lighting, and working alongside photographers. After all, Gavin has worked in all these areas at one time or another, and has done so since he was 15. He’s clearly happiest when he is doing multiple things.